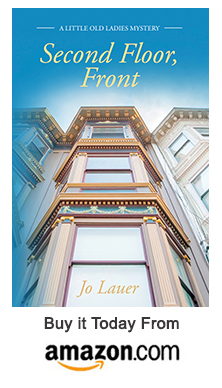

Current project (2023) – Adaptation from book to screenplay of Second Floor, Front. Goal is to convert the Little Old Ladies Mystery series to screenplays for episodic TV series.

Bits and Pieces

“Babe . . .” Wendy called as she stomped snow from her boots in the foyer before padding stocking-footed down the Italian-tiled hallway toward the kitchen. The strident chirp of a bird was the only response.

She stopped short and grinned at the profusion of red rose petals and brightly colored confetti that littered the entryway to the kitchen. “She remembered,” she said, her eyes moist with emotion. Wendy was a sucker for romance. Visions of chocolate dipped strawberries and champagne, brie, pate, and her favorite crispy crackers danced in her mind as she stepped lightly over the confetti and into the kitchen.

A chirp and a twitter greeted her from the cage on the countertop. “Can you say ‘Happy Birthday, my favorite person’?” she addressed Pesto, the green parakeet she’d purchased to go with the bright yellow kitchen in the apartment she found a little over a month ago.

Wendy cast a glance around the room. Not only was there no Xena, the current love of her life, and no strawberries—dipped or otherwise—the sink was still full of last night’s dishes abandoned in lieu of impulsive, hot sex followed by a shared bubble bath. Wendy grimaced at the marinara sauce tenaciously clinging to the white china plates. It almost canceled out the frisson of excitement at the memory of the preceding evening. Almost. She smiled.

“Xena?” she called into the emptiness of the rooms beyond the kitchen. Perplexed, she returned to the plethora of confetti and petals strewn about the hallway.

“Hunh,” she mumbled, as she bent down for a closer look. There were letters on eight of the tiny squares of colored paper which she carefully extracted from the mass. She returned to the kitchen and laid them out on the table like Scrabble tiles. “She knows I love a good game,” she said over her shoulder to Pesto, who squawked his agreement.

Crossword puzzles came easily to her, and her mind, trained to see patterns, quickly picked out the word ‘bitch.’ “Well,” she huffed, “that’s some birthday greeting.” There were three letters left. Her hand began to shake as she arranged them in front of ‘bitch’. Wendy gasped for breath as she read ‘die bitch’ spelled out in colorful confetti in front of her. She glanced furtively around the kitchen. The shades were drawn, the door to the patio locked. An ominous feeling of dread and danger began to seep its way into her muscles, and she hunched her shoulders self-protectively. She’d read in the tabloids about roommates who turn out to be serial killers.

It was true, she didn’t know Xena all that well—they’d only been officially dating for a couple of weeks. Xena had shown up last month to look at the apartment the same day as had Wendy. They had quickly acknowledged a mutual spark over dinner at an intimate little Chinese restaurant in the neighborhood. In fact, they’d gotten on so famously, they had decided to share the two-bedroom apartment. In her head she heard the exasperated responses by her straight friends when she told them she and Xena were moving in together. “You’ve known her how long?” was the now-familiar refrain, followed by snide references to the clichéd lesbian second date involving a U-Haul. Two weeks ago, the attraction between them had grown so intense, they’d waived the white flag and surrendered, trading in roommate status for something much jucier.

Wendy was deep in thought and didn’t hear the door at the end of the hall click shut, or the quiet footsteps approach.

“Happy Birthday!” Xena shouted, grinning broadly and waving a bouquet of iris in one hand and a dozen purple balloons in the other.

Wendy screamed. Pesto flapped about wildly in his cage, squawking and screeching hysterically.

Startled, Xena lost her grip on the balloons. They floated up to the vaulted ceiling and clung there as if in fear for their lives.

“What the . . .” Xena stammered.

“Stay back,” Wendy hollered, grabbing a spatula from the sink. She held it in front of her like a weapon. A dried noodle clung comically to the handle.

“Wen, get a grip. What’s wrong with you?” Xena, hands up in surrender, backed carefully away from her spatula-wielding girlfriend. “You’re freaking out the damned parrot,” she added.

“He’s a parakeet, you psycho,” Wendy retorted. “Do you want to explain this?” she shouted, jabbing the spatula at the lettered squares on the table.

Xena came forward carefully, not taking her eyes off Wendy. She glanced down at the table. “Die bitch? If this is some new game of yours, I don’t think I want to play,” she said.

“Game of mine? You left this for me in the hallway,” Wendy accused.

“No, I didn’t,” she said with an exasperated sigh. “It’s so like you to go to the worst case scenario.”

“What do you mean, worst case scenario? How else would someone interpret die bitch?” Wendy said, slowly lowering the spatula.

Xena reached over and arranged the squares to spell ‘itch’ and ‘bide,’ then rearranged them to spell ‘bit’ and ‘chide.’ She raised her eyebrows and shot Wendy a look.

The phone rang and Wendy jumped. She backed up slowly, still keeping her eyes on Xena, and reached her arm out to lift the receiver from the wall-mounted phone.

“Happy Birthday to you,” her mother sang, “Happy Birthday sweet daughter, Happy Birthday to you. Did you get my surprise?”

Wendy turned toward the wall and lowered her voice. “Did you leave it in the hallway?” she asked.

“Yes,” her mother said gleefully. “Wasn’t that fun? So when will you go?”

“Go where? What are you talking about?”

“The gift certificate for that 5-star restaurant you and what’s-her-name have been wanting to visit. What did you think I was talking about?” her mother sounded genuinely confused.

“Her name is Xena,” Wendy said, casting a quick glance back over her shoulder. “Hang on a minute, Mom,” Wendy said, and laid the phone on the counter. Xena looked at her quizzically as she rushed past her to the hallway. Wendy brushed aside the debris and retrieved a red envelop, camouflaged by the petals and confetti. She ripped it open, extracted the certificate, and squealed with delight as she ran back into the kitchen and grabbed the phone.

“Mom, this is wonderful! Thank you so much. But, I need to know, what’s with the lettered confetti?”

“The what?” her mother said.

“The confetti—it has letters on it, and . . .” Wendy realized she couldn’t begin to explain what she’d just been through.

“Oh, I didn’t realize that. It was sold by the ounce at the Smarty Party Store. I guess they recycle it. Honey, Harriet is honking outside—I’ve got to go. There’s a sale at Macy’s. Love you. Happy Birthday.”

Chagrinned, Wendy hung up the phone and turned back to face Xena.

“I think you can put the spatula down now,” Xena said.

Mudslide Surprise

Live as if it were your last day, you used to say. Who knew? I was supposed to die first. We used to joke about you poisoning my bran to collect the rest of my social security. There you were, at the bottom of that cliff—neck at an un-godly angle, body splayed like Dorothy’s house from The Wizard of Oz had just landed on you, your face too unrecognizable to register the unstoppable horror. Freak accident they said, bungee cords don’t usually snap. Little solace.

I’m thinking I have to get out of Dodge—too many ghosts staring at me blank-eyed.

Driving north toward The Gold Country, that trip we were going to take one of these days that no longer exist, I hear your voice saying, just follow your nose. Maps are for the weak and unadventurous, you’d say.

I’ve had enough adventure to last the rest of this lifetime, I would tell you if you were here. If you were here, I’d say you’re full of crap when you brought up the idea of jumping off that damn cliff.

Maybe I am afraid of my own shadow now. Maybe I’ve lost my grit. Show you who’s unadventurous. On a whim, I cast caution to the wind and turn our ancient faded blue Honda east on a rutted dirt road. This isn’t looking like a road that’s going anywhere useful, I’d say, if you were here. Barren fields to my left and right. Bumping along, clutching at the steering wheel, I’d say it’s looking like a dead end. I’d say this is probably the dead end of our fender wired onto the car after our last off-road adventure. Chicken, you’d say. Nothin’ wrong with chickens, I’d say.

Funny, a diner out here. The sign hangs at an odd angle. The Last Stop. I guess so. No cars around, just some dusty birch and poplars lining the dirt lot. The wood is silver from the weather. Doesn’t look like the place would stand up under a stiff wind. Side window is boarded up, and one railing is missing along those steps. Lights are on though. I could use a cup of coffee.

Hey, I say to the backside of the waitress as she busses dishes left by unseen customers. I walk over to the old wooden bar and hoist myself onto a stool. Reminds me of a ghost town saloon I saw once inColorado. Dusty bottles on an old plank in front of a faded mirror behind the bar. Part of me expects her to turn around and grin lasciviously at me with a zombie face and crazy eyes.

Hey, she says, friendly like. She’s no zombie, just some washed-out, middle aged woman stuck out in nowhere trying to etch out a living. You’re not from around here, she notices out loud. She tells me her name is Mavis and asks what she can get me.

There’s a jukebox across the room, the kind with the fluorescent colored lights and a stack of 45s playing something country. Back in the corner booth is a deranged-looking guy hunkered down in a pea coat staring at his hands clutching a coffee mug as if it were the only thing keeping him on the planet. He sits by himself surrounded by his own personal hell like the guys just back fromNam. He looks up with muddy eyes and hair that reminds me of a rabbit hutch.

That’s my brother, River, Mavis tells me. I nod. His blank stare slides back to his hands and that mug.

Coffee will do me, I say. How about a slice of Mudslide Surprise Pie she says. What’s the surprise, I ask. Wouldn’t be a surprise if I told you, she says.

I resist. I say something dumb about calories. She says something about living every day like it might be your last. Bring it on, I say, memories of you prickling my skin like gooseflesh.

Over coffee and pie, Mavis and I make small talk like strangers do. I ask could she point me to the Ladies Room before I hit the road. I leave a good tip with the bill on the bar and climb down off my stool.

I take two steps and my vision swims. My hands start to tingle and I grab at the lurch in my stomach with numb fingers. I try to call out, but no sound comes from my open mouth. My knees buckle, and from far away I hear Mavis say, Gotcha a new plaything, River.

Quilt of Souls

An attendant wheeled Cora into an office on the second floor of the hospital. “Good morning, Cora. I’m Doctor Morgan Craul. You may call me Morgan. I’ll be your therapist for the next few weeks.”

“Okay,” Cora mustered. She couldn’t keep her mind focused. Why was she here?

“Do you know where you are, Cora?” Morgan asked. Her voice was calming. She seemed genuinely concerned. Cora shook her head.

* * *

“Shhh, baby, baby, Momma’s sleepin’,” seven year old Natalie crooned to baby Landry who wailed crocodile tears from the folds of her blanket. Natalie brushed back frizzy hair, dry as September wheat, from her own face and tucked it behind a delicate ear as she bent to free the infant from her swaddling. The back of her hand felt the wetness of a soggy cradle sheet and her palm moistened with baby pee.

The room was as hot and stuffy as the inside of an old trunk. In the dim light that filtered through yellowing blinds, she could see bottles strewn about the carpet, leaking rank fumes and amber liquid. Landry continued howling like an alley cat in heat, her face red and swollen, her body hot as the July day. Natalie peeled off layers of blankets and threw them across the room in the general direction of the bucket. Baby pee didn’t smell so bad, she thought, as she laid Landry on a mostly clean towel, unlike the pee that puddles up under Momma. Dang, she wished she were at the swimming pool with Adele and Shank right now.

Out on the street she heard Butch, cussin’ out some poor bastard who happened to park in the curb space Butch considered his very own. She shook her head, the way a wet dog does, to try to get the sound of his voice out of her. When he had turned that shout on her, she had pulled so far inside she had nearly disappeared.

“It’s okay, Landry, I’m not gonna leave you,” she reassured the baby and herself. “You and me, someday we’re gonna get outta here, open us up an ice cream store, sell balloons and kites, too,” she sang the familiar mantra of better days ahead. She walked the baby across the room and back, picking her way carefully through the debris.

Landry, quiet now, stared up at her with eyes that were dark mirrors of fear and dread. Her tiny mouth sucked silently on her thumb as if it offered sustenance and protection from the evil such a small a being should never have known.

An ambulance careened into the alley. The scream of the siren cut through the summer dusk scattering children playing Kick the Can, neighbors catching the first waft of cool evening breeze from the cement steps out front, and stray cats rubbing against overflowing garbage pails. Bodies dispersed only to reconvene in morbid curiosity as the paramedics rushed up the steps of the brownstone.

“Stand back, folks,” Ed Fontaine used his bulk to clear a path to the open door of Number 11. He usually worked crowd control, leaving his partner La Rue quick access to triage. Ed had never developed a stomach for being the first on the scene.

“Oh, pee-euw!” said old Mrs. Hickey from across the hall. She reeled against her doorframe and covered her mouth and nose with the back of her liver-spotted hand.

From the far reaches of clouded consciousness, Cora heard Butch’s voice full of venom hiss, “Go on bitch, die. Do the world a favor.” Cora tuned her head to pull away from his voice.

Cora’s mind was like a battlefield, broken bodies, fragments of souls, pieces scattered everywhere.

She didn’t know what was happening to her. Then, from nearer, “On my count—one, two, three…” and Cora’s body was shifted onto a hard surface. Then blackness.

In the ambulance, La Rue called in their ETA along with the alcohol and barbiturate overdose of 54 year old white female, Cora Buckley.

* * *

“Amen,” whispered Marvel as she finished her daily prayer for Jazelle’s soul and blew out the white candle on her altar. A slow drip of molten wax worked its way down the candle and melded into the silk scarf she used as an altar cloth.

The acidy sounds of The Jefferson Airplane’s White Rabbit blared from shabby speakers which balanced on a warped board that had once served as the dining table. They never ate at the table, as Jazelle preferred to use a collection of TV trays that she’d decoupaged with pictures of bejeweled, toothy actors and actresses from her movie magazines.

Jazelle exhaled sweet, pungent smoke from her nose, leaving vapor trails in the air. “And the ones your mother gave you don’t do anything at all,” she sang in a sultry Grace Slick impersonation. Her big gold hoop earrings bobbled against her chin as she shook her head, and flung her sleek black hair over her shoulders and back again. Enough of all this gloom and doom; she was having herself a par-ty. “I am not a whore,” she shouted, and shook her head to get rid of that voice.

Baby Landry’s red-eyed gaze looked detached and far away through the cloud of smoke, but she was quiet now.

“Would you like to light a candle and pray for anyone, Natalie?” Marvel offered. “I’m praying for Cora. I figure she could use all the prayers she can get, locked up in that hospital.

“I don’t have much use for prayer,” Natalie said, keeping her voice even. “What kind of God would let this happen anyway?”

“Saint Marvel probably has an answer for that, don’t you Marvel?” asked Jazelle in a dreamy voice, swaying to the music in the middle of the room with the baby in her arms. The infant’s limbs hung limply and wobbled to the beat.

“God works in mysterious ways,” Marvel’s voice was full of quiet conviction. “I believe She’s working through us right now, to bring strength and hope to Cora,” she said. “I forgive you,” she said, turning her head away from the sting of an insult not heard by others.

* * *

Across town, in a dimly lit back room of the Psych. Ward at St. Boniface, Cora stirred in the muss of sheets, wet with sweat and tears. Her own stench made her nauseous.

“Damn, that was a stupid thing you did back there. You could’ve burned the whole place down with that lit cigarette that fell on the floor. What a cow,” Butch spared no mercy.

“Shut up! Shut up and go away. Leave me alone,” Cora managed to rasp out through a parched throat. Her scalp itched and the skin on her face burned. Every muscle felt as though it had been stretched taut then let go. She took the fear and despair she felt, loosened a brick in the wall of her emotional well, stuffed the feelings in, and tamped the brick securely back in place.

“You wouldn’t last a day without me, you idiot. Who the hell you think takes care of things when you’re shit-faced? I don’t know why I bother with the likes of you,” he harangued.

A young nurse with pale blonde hair entered; her long braid swung as she crossed the room. She scribbled notes in a manila chart, and checked the white paper pill cup to make sure it was empty. She made no eye contact, didn’t speak. Cora sensed that the woman was holding her breath.

“Could I get a drink—Cait?” she asked, noting the nurse’s name badge.

“Yeah,” Bert whispered, loud enough for only Cora to hear, “just throw a liter of whiskey in the bag. Heh, heh. Cait,” he smirked, “not K-a-t-e, but C-a-i-t. Sheesh. Must be from California.”

Cora’s head was pounding. Cait Plunkett, LVN, answered in a voice that felt like Graham cracker crumbs in the bed. “Ice, you can have ice,” she said, looking at Cora’s chin. She turned abruptly and left the room. Cora felt humiliation burn her face. Obviously, Cait had taken offense. She didn’t know anyone else could hear Bert.

“Flo Nightengale she ain’t,” muttered Butch.

“Leave me alone!” Cora shouted, pressing her temples and squinting against the pain.

“You don’t speak to me like that, woman.” Butch was on her like a junkyard dog. Before she knew what was happening, he had yanked her by the arm out of bed and onto the floor. She heard a soft thud on her way down as her head met the corner of the drawer that had been pulled out from the bedside table. Blood oozed down the front of her white hospital gown. Her vision blurred and a searing pain finally caught up with her.

A keening cry that Cora didn’t realize was her own, brought an attendant on the run, followed by Nurse Plunkett. Butch had vanished.

Back in the apartment, Natalie sat on the edge of the bed, rocking back and forth. “She’s not coming back, I know it,” she cried. She had used up all of her patience trying to calm Landry who had kept up a steady wail for the last hour. Her nerves were shot. She was scared.

“Oh, she’ll be just fine,” Jazelle patted her leg. “Have another brownie. You want more Coke?” she asked as she reached for a tube of lipstick on the nightstand. With a deft hand, she applied a layer of ice-pink over her lips, followed by another, and another. She flashed a butter- cream frosting smile at the mirror.

Natalie felt the mattress indent as Marvel curled up behind her, wrapped her arms loosely around her and whispered in her ear, “Pray with me.”

“Oh for heaven sake, Marvel, why don’t you pray that baby shuts up pretty soon or we’ll all be in the nut house!” Jazelle said.

As if plugged into an invisible battery, Landry launched into an even more vigorous outpouring of ear-splitting, raw emotion. Natalie sobbed quietly; Marvel began a “Hail Mary;” Jazelle reached for her nail polish; and in a hallway of St. Boniface, Butch swore under his breath, “I’ll show you who is boss. Next time I just might kill you.”

* * *

“Could you tell me where you are please,” Morgan was more specific this time. She looked into eyes that shifted like sand in the dunes. She knew that look.

“Damn, lady, if you don’t know, you’re in worse shape than I am.”

Morgan blinked at the deep voice, the hostile tone. She drew in a slow breath, settled back in her chair and said, “Hello, I’m Morgan. What may I call you?”

“You may call me a cab so I can get the hell outa here,” Butch answered. “She doesn’t need you, so why don’t you go do your do-gooding somewhere else, okay?” He leaned forward, hands braced on the seat of the couch, as if readying himself to lunge. The transformation was remarkable.

“Who else do you speak for?” Morgan asked. “May I speak to another?” She waited and watched the shift of energy, the carriage of the body, the melding of the eyes from one personality to another.

Unguarded tears ran from the eyes of the exhausted child who appeared before her.

“I can’t make her stop crying,” she said in a small voice. “I don’t know what to do,” she sighed, and pulled her legs up onto the couch, hugging them close to her body with her arms.

“How old are you, and what may I call you?” Morgan asked softly.

“Natalie. I’m seven. And I have to take care of baby Landry.”

“That’s a terribly big job for a seven-year old girl. Do you have any help?” Morgan prompted.

“Jazelle is supposed to be watching us. And Marvel.” Natalie blew her nose with the Kleenex Morgan handed her. “But they’re really not much help,” again, a jagged little sigh that sounded like a whimper.

“I’d like to be of help, if I could,” Morgan offered. “Do you suppose I could speak to Jazelle or Marvel? And, I’d like to talk to you again in a bit, if that would be okay.” Morgan wondered what trauma had left a seven-year old in charge of the system.

The gate was open. It was unusual to have so much revealed at the first session. Morgan also wondered if Cora had any idea.

Quilt of Souls was published in Vintage Voices: Words Poured Out—An Anthology of Writing by Redwood Writers, a Branch of the California Writer’s Club, 2010

Satellite People

This is not a story about outer space. It is, perhaps, a story about inner space—that space between consciousness and heart where a handful of people dwell. They are people on the perimeter of my urban life whose faces are as familiar to me as relatives who live across country. They are not the folks I’d ask over for dinner or to a movie. Yet, I count on them. Somehow, they shape my reality.

Bunker Man molds his body into an “L” shape, with legs stretched out on the cold cement stoop and back flat against the side of the faded brick building. A tattered ski cap the color of mildew covers his graying hair. A faded pea coat, like the ones we wore back in the ‘60ies at antiwar rallies in D.C., is his cover, his bedding, his tent.

Every Saturday morning I walk into town to mail my bills at the post office and deposit my checks for the week at the bank. I could mail my bills from home and bank on-line, but it’s my way of shrinking a large city into a small town, like where I grew up.

Each Saturday I pass Bunker Man, holed up, keeping an eye on the streets. We never speak, but we nod in recognition. His pale blue eyes sparkle, incongruent with the flat affect of his body. Or perhaps it’s the sun glinting off the leaves of the crape myrtle overhead.

I am consumed with curiosity about his life. Does he have children? Has he lived anywhere other than against the brick building? What has life presented him with that he sits, day after day, watching? I will never ask. The rains have come and the temperature dips low at night. Where has Bunker Man gone?

Then there’s Jean. I don’t know why I think of her as Jean, no one ever spoke her name in front of me. Jean walks. In her natty old black ankle-length trench coat, she walks the streets of the city with her zombie-like gait, eyes fixed on the pavement three feet in front of her. Her straw-colored brittle hair is covered with a non-descript scarf, faded and jagged at the edges, knotted under her chin. Her mouth works itself in a tartive sort of way, soundless, mysterious. People shrink back slightly as they pass her, their nostrils narrow a bit as if readying themselves for a sour smell.

I smile when I pass her at one end of town or the other, marveling that she arrives on foot before me at the places I drive on the hottest, the coldest, and the wettest of days. She does not return my smile. She does not know I take comfort in the familiarity of her, or that I worry about someone harming her.

Jesus walks about town wrapped in a white sheet and little else. His beatific smile and golden curls remind me of a Renoir painting. His eyes are large blue saucers fringed with delicate blonde lashes. He carries a leather-bound Bible and blesses people. “Thank you,” I say. You can never have too many blessings. I wonder, in the cold months, will he don shoes and a coat? Does Jesus wear long johns?

For several weeks of my Saturday trek into town, Bunker Man hasn’t been on his stoop. The first week I thought perhaps he’d scraped together enough spare change to step out for a cup of coffee. The second week I looked around his “spot” for clues of his presence, and found none. This, the third week, I stick my head into a small shop next to the stoop.

“The guy who lives just outside your shop on the stoop . . .” I begin.

“Oh, yeah,” the shop owner smiles, “he’s gone.”

My heart pounds. What fate has Bunker Man met, and why is this callused man smiling at his absence? Glad, perhaps, to be rid of another piece of urban blight next to his doorway? I set my jaw and narrow my eyes.

“Yes, I noticed that. Do you know what happened to him?”

The shop owner walks over to the door and leans against the frame. “His family came fromOregon. Brother and Mom, I think. Said they were going to take him home, that they had a trailer on some land for him. They’d been worried about him so far from the family.” The shop owner’s eyes are moist, and a soft smile plays on his lips. “I kinda miss the guy,” he says.

“Yeah,” I swallow around the lump in my throat, “me too.”

We stand for a moment, there in the doorway, honoring the memory of an enigmatic soul who’d been brought back into the folds of family. Instead of mourning an ending, we celebrate a new beginning. May life be well for you, Bunker Man.

The Three Muses

The hoot of a barn owl and her own reflection against the black night on the other side of the sliding glass door startled Winnie. Her hand jerked and Merlot leapt from her goblet onto the carpet where it was absorbed like quicksand by the cream-colored wool.

“Stupid chicken shit!” Winnie hurled at the night sky. The words ricocheted off the glass pane and splattered all over her.

“Get a grip,” she muttered to herself as she uncorked the bottle and refilled her goblet for the fourth time.

Winnie’s armpits itched and a rancid odor wafted up when she lifted her elbow. She yanked a cord and drew the vertical Venetians closed, and then stumbled toward the utility room for spot remover. Her eyes caught the slight movement, a shift in the corner of the darkened room. She set her goblet on the window sill.

Holding her breath, she took a step backward. The wood planks beneath the worn thin carpet creaked under foot and she froze. Winnie ran a hand along the wall until she reached the light switch, dreading, yet compelled to illuminate the bogeyman hiding among theHooverattachments.

With a shaking finger, she flipped the switch. A glare of white light from the bare 100 watt bulb above her head flooded the room.

“Jesus! You could blind a person,” hollered the bag lady like visage in the corner shielding her eyes with a bony hand. She was older than dirt, dirtier than dirt too, it appeared. She wore a ragged housedress of faded indefinable print and a tattered musty sweater several sizes too large for her scrawny frame.

Her sparse white hair spritzed out in all directions. Her eyebrows, same color as her hair, were like two fat caterpillars napping above rheumy blue eyes that squinted out under heavy lids at Winnie.

“Who the hell are you?” Winnie gasped, holding one hand over her palpitating heart. “And what are you doing in my utility room?”

“Relax, missy, I’ve been sent,” the woman croaked as she stepped out of the corner, over the attachments, and dusted herself off as best she could.

“I’d planned to land on the porch. Guess I’ve lost my night vision. Call me Gwynyth,” she said, extending a liver-spotted hand with dirt encrusted fingernails.

“What do you mean you’ve been sent?” Winnie recoiled. Her nose wrinkled and her mouth tightened with judgment.

“Think of me as your guardian angel,” Gwynyth said. Her crooked smile was missing a few teeth. She dropped her hand to her side, noting that this woman was not the friendly type.

“I don’t need a guardian angel,” Winnie said in a huff. “And, if I did, I certainly wouldn’t choose you!” She pulled herself up to her full 5’5” stature and stared down her nose at the old woman.

“Oh, you don’t choose us, dearie, we’re assigned.” She took Winnie’s elbow and spun her around toward the bedroom door. “I musta really pissed off the boss to pull this assignment,” Gwynyth said aside.

“Unhand me!” Winnie cried out. “What do you think you’re doing?”

“You left a mess on the floor in there. Thought I’d sort of show you my credentials,” she said as she ushered Winnie, protesting all the way, back into the bedroom.

Gwynyth pointed at the blur of red wine diffused among the fibers of the carpet. “Spit clean,” she uttered. The spot vanished.

“My god, you’re a witch,” Winnie whimpered.

“Nah, that was another lifetime,” Gwynyth smiled amicably. I’m here to help you clean up the mess you’ve made of your life, help you with your problems, and stuff like that.”

Winnie brushed a stand of her own graying shoulder length hair back from her face. “I’ll have you know my life is NOT a mess, and I have no problems.” This creature was working her last nerve.

“Well, here’s one problem—your bed faces West,” Gwynyth sighed in disgust, shaking her head slowly.

“What’s wrong with West?” Winnie asked in spite of herself.

“Sun rises in the East. Hell, at your age, just to know you made it to the next day when you open your eyes has gotta be worth something,” Gwynyth cackled.

“At my age? I’m only sixty-two,” Winnie hoisted her chin.

“The Golden Hours,” Gwynyth continued, ignoring her, “ that’s what you want to be waking up to—watching the sun rise, bringing in a new day, fresh start, clean slate, all that crap.”

Gwynyth tugged at the cord and whipped the vertical Venetians open.

“Yikes!” she yelped at her own reflection.

Gwynyth pulled, grunted and groaned until the rounded brass foot of the bed was aimed squarely at the sliding glass door where the earliest rays of tomorrow’s sunrise could not be missed. She wiped her hands briskly on her faded dress and surveyed the room. She lifted the ceramic goblet from the windowsill, slid open the glass door and heaved the contents out into the night.

“That was a perfectly good glass of Merlot you just wasted,” Winnie complained.

“Stunt your growth,” Gwynyth retorted.

“I’m sixty-two—there’s not a lot of growing I’m likely to do,” Winnie groused.

“‘Sup to you,” said Gwynyth. “A friend of mine said ‘whether you believe you can or believe you can’t, you’re right’. I’m here to convince you you’re not done yet.”

“A moment ago, you had me on the very brink of death,” muttered Winnie. She yawned and sat down heavily on the bent wood rocker next to the bed. This had been a very tiring evening.

“I was just messin’ with you,” Gwynyth said as she bent down to remove Winnie’s slippers. She turned down the blankets on the bed, fluffed the pillow and reached out a hand to Winnie.

“Beddie-bye time,” she said.

Too tired to resist, Winnie allowed herself to be pulled to her feet, and guided into bed where the covers were tucked up under her chin. As her eyes closed with the heaviness of sandbags, she decided this had all been a wine-induced hallucination. Things would look better in the morning. Across the room, the light clicked off softly and the last sound she heard was the shuffle of feet leaving the room.

Somewhere in the neighborhood a rooster crowed. Winnie twitched the muscles of one eyelid, then allowed a crack of vision. A blaze of peach, melon, and mauve lit the morning sky. Before she could clamp down on it, a smile played at the corners of her mouth.

“Stunning, ain’t it?” Gwynyth’s voice crackled next to the bed.

Winnie jolted upright, groaned, rubbed her temples then collapsed back against a just-fluffed pillow propped against the head of the bed.

“Quick—what do you hate most?” Gwynyth demanded.

“Living a meaningless life,” Winnie said. Startled by her own vulnerability, she yanked at the flannel sheet and swiped angrily at the tears rolling down her cheeks. “Not fair,” she hissed.

“When you first wake up your defenses are down. That’s when I can get an honest answer out of you. By the time you leave the house, you’ve already got your armor on,” Gwynyth explained.

“Why are you still here?” Winnie groaned.

“Told you. We have work to do. Fresh start, new day. Today’s the first day of—”

“Don’t say it,” Winnie warned.

Gwynyth produced a bamboo tray laden with English muffins topped with cream cheese and marmalade, three crisp strips of bacon, orange juice, coffee and a multivitamin. A colorful cloth napkin was folded into something resembling a giant bird that stood watch over the food. The smell of hot coffee made Winnie’ stomach rumble.

“Eat up. The others should be here soon,” she said.

“Others? What others? You can’t just invite people into my home. My god, the sun’s not even all the way up yet,” Winnie sputtered.

At just that moment, a rumpled heap landed with a thwump on the deck just beyond the sliding glass door.

Winnie shrieked.

“Musta lost her landing gear,” Gwynyth mumbled as she opened the slider.

She watched as AfroDidee chortled, pulled herself to her feet, rearranged her face into a big smile and hollered, “Gwynnie!”

The two old women fell all over themselves in a clumsy, bear like embrace.

“Ya don’t look a century older than the last time we worked a gig together,” AfroDidee wheezed. “Creation sends her regards,” she reported to Gwynyth. “She got busted in a Save-the-Redwoods rally inSan Francisco.”

“That girl always has a cause,” Gwynyth nodded respectfully.

Winnie, sitting propped up against the headboard, watched wide-eyed as Gwynyth and her friend entered the bedroom.

“Winnie, this is AfroDidee, Goddess of Luv,” she said, making a grand sweeping gesture toward the old woman whose steel gray hair looked like an electrocuted Brillo pad. She was dressed in a ‘Go Raiders’ sweatshirt, an adult diaper covered with colorful Valentine’s Day stickers, and red sneakers.

Her walnut-colored eyes twinkled in her leathery face as she dipped a quick curtsey and said, “Hi-dee.”

“No, it’s Winnie,” Winnie corrected. “She’s wearing diapers,” Winnie stage whispered to Gwynyth.

“I can take ‘em off . . .” AfroDidee offered.

“Oh, god no—please!” Winnie covered her eyes with shaking hands.

“I meant the stickers,” AfroDidee explained to Gwynyth, her voice apologetic. “You know, for different seasons.”

Gwynyth patted her arm. “It’s okay, she’s just a little jumpy,” she reassured her friend. They both regarded Winnie who was now squinting through her fanned fingers as if watching a horror show.

A rap on the glass slider startled the trio.

“Hey, hey, what d’ya say . . .” a voice boomed on the other side of the door. “Open up or I’ll go away.”

“Fate!” both Gwynyth and AfroDidee called out.

Gwynyth slid the door open and pulled a stout old woman in a large straw hat into the bedroom. She wore a flowered muumuu and rubber flip-flops. Her skin was the color of hickory and her hair was died deep auburn like the last rays of sunset.

“Did I miss anything?” she asked, a righting the hat that had been knocked askew by the doorjamb.

“This here’s Winnie,” AfroDidee pointed to the woman who had pulled the quilt up under chin and held it there with a death grip.

“Fate’s the name, intervention’s the game,” she said by way of introduction. She turned to Gwynyth and said, “What’s wrong with her?” She crooked her head to once side then the other, studying Winnie from different angles.

“Nothing’s wrong with me except I have a room full of lunatics and I haven’t even had breakfast,” Winnie squawked.

Fate munched thoughtfully on a marmalade-spread muffin.

“I think we need a game plan,” she said. “Did she come with instructions?”

“Why me?” Winnie moaned. “Why not Mrs. Rosenblatz down the block?”

“Mrs. Rosenblatz doesn’t hate her work and drink herself silly at night or spend her weekends watching bad television all by herself with the blinds pulled,” Gwynyth explained in a reasonable voice.

“Can I help it if I’m trapped in a crappy job? I don’t have a college degree and I couldn’t run a computer if my life depended on it. My lousy ex-husband left me penniless, the bum. If I had any money, I’d retire. If I had any sense, I’d kill myself,” Winnie ranted. “So I drink a little bit at night to brace myself for the next day. So what?” she challenged.

“Hey, you are the weaver, you are the web,” AfroDidee offered.

“What on earth is that supposed to mean?” Winnie asked.

“We create our own reality by the choices we make, and then we’re stuck with it until we make new choices,” Gwynyth answered.

“All roads lead toMecca,” added Fate.

Winnie scowled.

“Or, you might say,” Gwynyth explained, “there is a master plan, but how you get to the outcome is through a series of making one choice after the next.”

“Each choice has its own consequence,” Fate added.

“It’s like when you married Harold back in the ‘60ies. Remember? You wanted to be a librarian but you couldn’t afford to finish college because he couldn’t keep a job,” Gwynyth tsked.

“Harold was a toad,” Fate muttered. “A mere stumbling block on your path, but you gave up on yourself.”

“You mean I’m responsible for the way my life looks?”

“‘Fraid so, kiddo,” chirped AfroDidee.

“If you had your druthers, what would life look like?” Fate inquired.

“My druthers?” Winnie sneered. “Well, I’d be lounging on aSouth Seasisland with my wealthy husband, sipping one of those drinks with the umbrella in them. Why?”

“And that would be a meaningful life?” Fate asked.

“Look, you’re Fate. You already know the future. Why not just cut to the chase?” Winnie asked in a pique.

“Well, I’m not really supposed to do this, but you are one pathetic case. Maybe just this time.” Fate pulled up a chair opposite Winnie. “Remember, how you get there is up to you.”

Winnie sat up straighter in bed. She had to admit; it wasn’t every day that Fate just laid it on the line for you.

“Okay, you’re not so far off. I do see you on aSouth Seasisland with your husband. He seems to be a native there.” Fate squinted her eyes and peered into the distance. “You’re finally doing what you were meant to do. You have a fair amount of notoriety on the island,” she finished. “Whew! Plumb wears me out,” she muttered.

Just then, the phone on the nightstand trilled. AfroDidee lifted the receiver. “Winifred’s residence, AfroDidee, Goddess of Luv speaking. How may I help you?”

A pause while AfroDidee nodded her wiry hair.

“One moment please,” she said grinning hugely, “I’ll connect you.” She handed the phone to Winnie, gave a palms-up shrug and said, “Looks like my job is over.”

“No fair,” Fate mumbled. “You didn’t even break a sweat.”

On the phone, Winnie was saying, “Palo? Yes, of course I remember you. Well, how very nice of you. Tomorrow night? Oh, my. Let me check my calendar and get right back to you.”

They exchanged a few more pleasantries, before Winnie hung up. She sat in stunned silence.

“Are you going to leave us here dying of curiosity?” Gwynyth asked.

“How strange is that?” Winnie said. “I thought he moved back toFiji. The man I met at my aunt’s funeral three years ago just asked me out to dinner.”

* * *

Remnants of breakfast remained on the tray. Gwynyth finished the cup of coffee. Fate wiped a bit of bacon from her lower lip. AfroDidee set the juice glass down carefully. Winnie swallowed the last of her muffin.

Gwynyth leaned against the pillow at the head of the bed, her sweater draped over her shoulders. Fate propped herself against the foot with her straw hat perched on bent knees. AfroDidee rocked in the wooden rocker, a blanket snuggled over her lap, her red sneakers resting near the nightstand. It looked like a pajama

party for the demented.

Winnie perched on the edge of her bed, held her robe closed with one hand, and gestured wildly with the other as she spoke.

“I can’t just have dinner with a man I barely remember,” she said, with an openhanded smack to her forehead. “I’m sixty-two, I’m fat, I’m wrinkled, I’m gray . . .”

“I’m waiting to hear something that matters,” AfroDidee offered.

“What was it he saw in you three years ago that would lead him to call you out of the blue?” Gwynyth asked.

“He said he like my droll humor,” Winnie smiled in spite of herself. “And we talked about poetry, right there at the graveyard, waiting for my poor aunt to be planted in the ground,” she shook her head in wonder.

“Sounds like he was looking at the inside of you while you seem determined to focus on the outside,” Fate offered. “Which, by the way, there’s nothing wrong with the outside of you,” she added.

“Go ahead; choose happiness just once for yourself. Step outside the box and take a little risk,” Gwynyth urged.

With a trembling hand, Winnie lifted the phone and dialed, amidst smiles and winks all around her.

* * *

The three old women sat slumped around a wrought iron table on the plaza, lulled by the noonday sun, the trickling waters of a nearby fountain, and an icy pitcher of Margaritas which sweated an ever spreading circle on the checkered tablecloth. A multicolored umbrella turned lazily overhead.

Gwynyth smiled and refilled her own glass before passing the pitcher on. Fate, sporting an Easter bonnet covered in bright azaleas, fanned herself with an envelope while Gwynyth unfolded a letter, hand written on cream colored stationery. AfroDidee laid two glossy photos on the table. One was of a clump of children, Winnie, and Palo in front of a small wooden building with a brightly hand-painted sign that read LIBRARY just above the door. The other was of Winnie and Palo sitting on beach chairs at the water’s edge, smiling at the camera, each holding a tropical drink with a tiny umbrella.

Gwynyth took a gulp of her Margarita before reading the letter.

Dear Ones, she began. “Ah, she called us dear ones.” Gwynyth stopped, sniffed, and blotted a tear that trickled down her cheek. Fate moved the pitcher of Margaritas to the other side of the table. AfroDidee poured herself another glass.

Greetings from the South Seas where Palo and I have opened a small library on the island, with guess-who as Head Librarian? I’m also teaching English as a Second Language to the children. I couldn’t be happier…”

“Ah, she couldn’t be happier,” Gwynyth dabbed at a tear and blew her nose.

“That’s our girl,” Fate said.

“She looks kinda blissful, doesn’t she?” AfroDidee observed.

I’ve truly found my bliss, Gwynyth continued. She raised her eyebrow at AfroDidee.

“Hey, it didn’t hurt that you pulled Palo out of thin air just when you did,” Fate addressed AfroDidee.

“I thought you did that,” AfroDidee looked at Fate.

“What’s that little word on the bottom of the picture?” Fate squinted.

“Over,” said AfroDidee, flipping the photograph.

Here’s to better choices. Love, Winnie p.s. those are virgin Mai Tais.

“I’ll drink to that!” smiled Gwynyth.